I can usually tell pretty much how much wine I've had over an evening, even when a solicitous waiter has done the pouring, by how much elbow-bending I've done and how it makes me feel. In Dominicanomics, I spend a lot of time talking about liquidity in the Dominican banking system, but I've no more been able to measure that than the wine I've drunk. As with wine, though, I have an idea what it looks like and can see its effects...and work backward from there.

In principle, it is a pretty straightforward concept. It is the amount of central bank liabilities (cash and deposits held at the central bank by the private sector, mainly banks) beyond what is required by various regulations. Mostly, this means the reserve requirement, a rule that makes banks hold a fixed percent of deposits on deposit at the central bank (details vary by country). In the Dominican Republic, it gets more complicated.

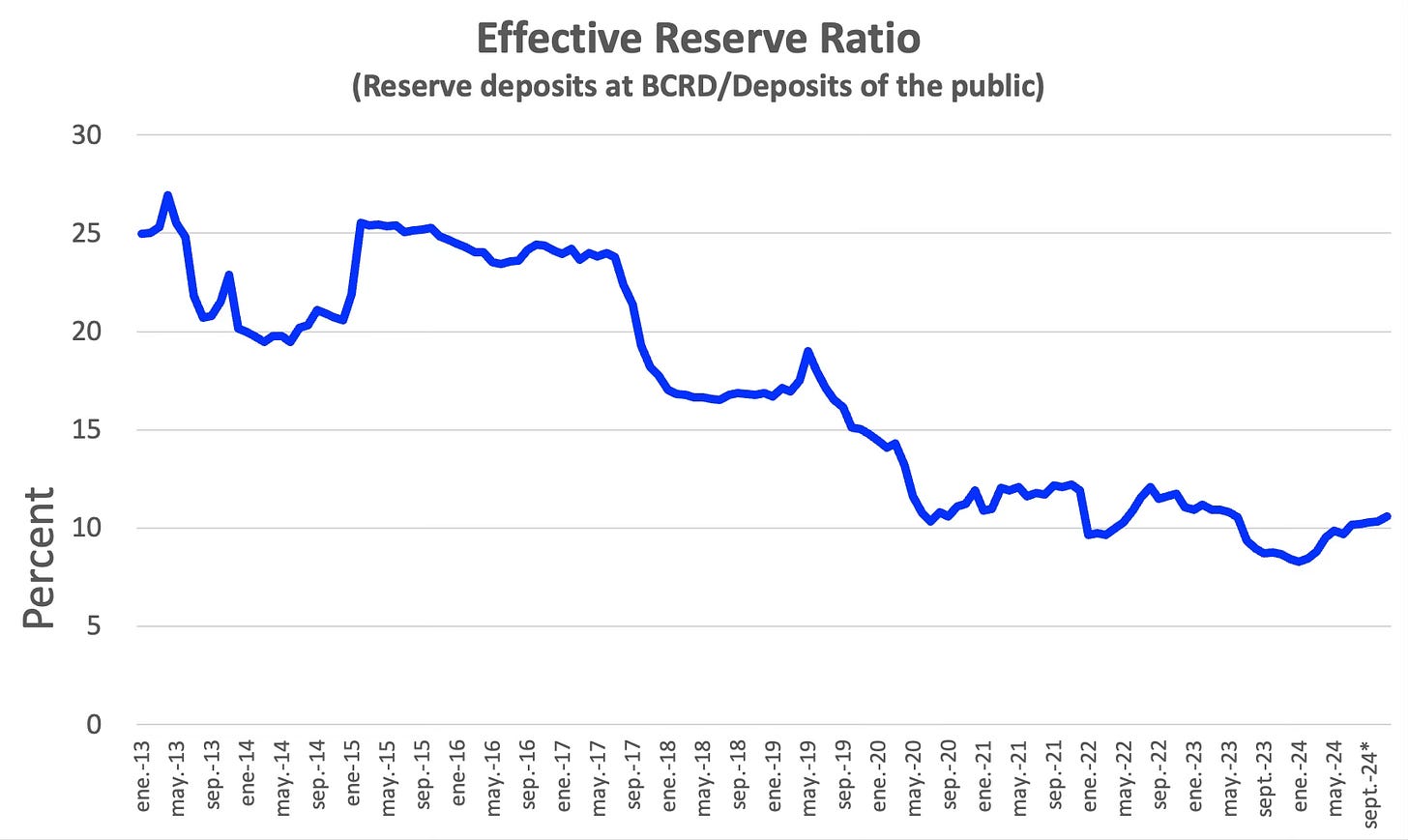

From time to time, and on average about once a year, the BCRD plays with this requirement. Sometimes they formally change it, and sometimes they manipulate it: the Bank simply tell commercial banks (and other deposit-taking institutions, like savings & loan institutions) that they can make a certain amount of new loans for specific purposes while still counting them as being held in their deposit account at the BCRD as required.

Sometimes this "liberation" of required reserves is permanent; sometimes it needs to be returned to the bank's account at the BCRD at the end of a specific term; and sometimes it can be rolled over, as I understand it, into another priority loan of the same type (these are most often for the construction of "low-cost" housing, for agriculture, or for "productive sectors", and even, occasionally, for consumer loans). Once those loans are repaid, the money typically needs to go back to the BCRD for real, but sometimes it can be relent.

Each time, all of this is set out in a resolution of the Monetary Board (the Junta Monetaria). The Monetary Board generally doesn’t publish its resolutions. The BCRD used to publish a selection of important but not-so-sensitive resolutions, but no longer. (It has replaced that with a search engine that doesn't find anything. Don't believe me? Try it yourself: https://bancentral.gov.do/a/resoluciones. And if you come up with something, let me know!) I have collected what I can figure out in the table below.

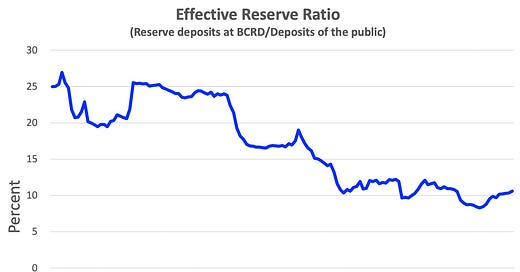

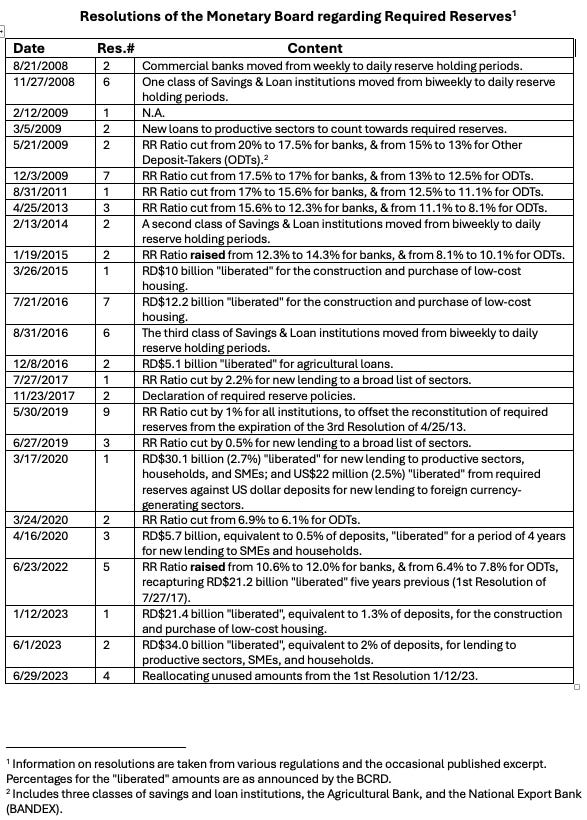

The end-result is that the true level of required reserves at any point in time is virtually impossible to calculat.1 The required reserve ratio seems to have been about 12% for commercial banks and 8% for the others until last year, when they dropped by around 3 percentage points, based on the amounts "liberated". The deposit account at the BCRD in which the required reserves are held has had amounts equal to slightly above 10% of deposits in recent months. But without knowing how much of this is required--and this changes daily--and how much is available for other purposes, I just can't say what liquidity is.

Why doesn’t the Monetary Board just adjust the ratio when it wants to affect liquidity?First, by making it impossible to see what is really going on, it insulates itself from criticism. But then by “liberating” a fixed amount of required reserves, the “liberated” amount becomes a smaller and smaller share of total deposits over time, thereby raising the effective required reserve ratio. This, in turn, gives the BCRD regular opportunities to “liberate” even more funds (and to issue a press release about it), building its reputation as a champion of easier monetary conditions: as with the TPM (the monetary policy interest rate) that I have written so much about, the BCRD can look like it’s doing one thing while doing something more politically convenient.

The current Governor hasn’t been renominated a dozen times for no reason at all!

I may try again at some point, but the calculations are involved, and necessarily approximate.