In November, for only the third time since 2012, the average loan rate at Dominican banks topped 16%. I have said many time that the lowering the Monetary Policy rate (TPM) and expecting loan rates to decline is basically wishful thinking. I have said that "liberating" required reserves is not a good idea, either. These are the headline measures being taken by the central bank. What really can be done?

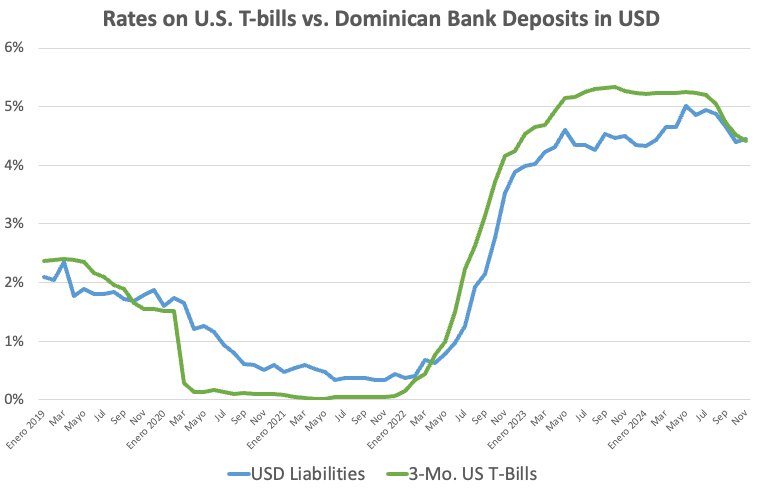

As we saw last time, time deposits in US dollars in Dominican banks attract interest rates pretty similar to the rates on U.S. Treasury bonds:

Notably, the banks have managed to go from paying a premium to T-bills to getting a discount from depositors on the rate they are paid. How did they do that? I suggest that this was largely by reducing the riskiness the deposits they take, maintaining a capital/asset ratio (the ratio of the banks' shareholders' money to the total amount they are managing) of around 17-18%. The legal requirement is only 10%. Recent stress tests by the IMF could only get that ratio down to around 12% in the face of an imagined crisis.

When I talk about the trilemma, I often take open capital markets as a given, leaving the central bank a simple choice between deciding on the exchange rate or deciding on monetary policy. I think that's fair, given that the last person to try to limit capital flows was President Balaguer in the 1980s, and that failed rather miserably.

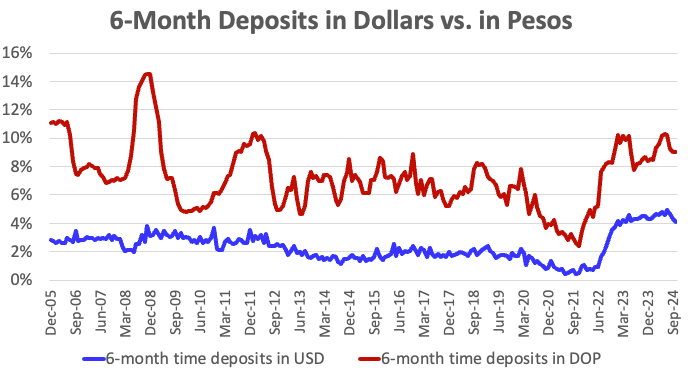

Depositing dollars in Dominican banks spares depositors from exchange rate risk, but the majority of deposits are in pesos. For that, the banks need to pay a considerably higher rate:

The 2008 Global Financial Crisis undermined confidence in the ability of the BCRD to meet potential capital flight, and so the currency premium rose above 10%. The average rate of actual peso depreciation over the last 5 or 10 or 15 years has been about 3%. So there is a risk premium, currently about 2%, paid to depositors to compensate for the risk that the peso would depreciate more than the usual 3%. This premium is held down, in part, through the large foreign exchange reserves held by the central bank, and its demonstrated determination to limit depreciation to around the usual amount. Those reserves also give confidence to depositors that they stand a good chance of getting their money out of pesos should they elect at any point to do so.

Bankers may also be encouraging the BCRD to hold its current high level of international reserves: they cannot make country risk go away, but they can reassure depositors that there are plenty of dollars available if they ever do want to get their money out of the country.

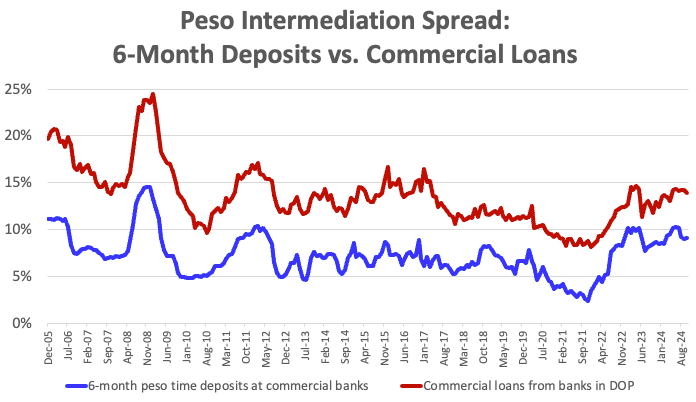

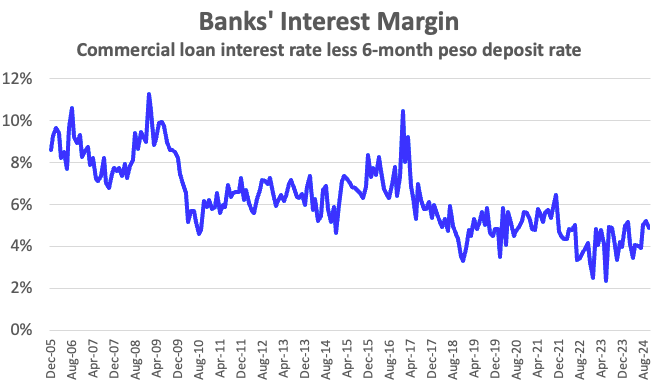

Finally, the other element that goes into lending rates is the banks' own spreads, also currently around 5%:

This spread varies, across time and across banks, but has come down over time, as we can see more clearly here:

Now, 5% is still quite wide. Bank profits are, on average, about 3% of assets here, so loan rates could all come down by about 2%, and banks, especially the larger ones would still be quite profitable, earning perhaps 1.5% of assets in profits. I asked ChatGPT what was a "reasonable ROA" around the world, and the answer was that 1.5% was high for Europe, and pretty much normal everywhere else, including Latin America.

Cutting bank profitability in half is easy to imagine, difficult to do, and possibly with undesirable side effects. Still, it is indicative of where there could be room for interest rates to fall, in addition hoping for a decline in U.S. rates, which doesn't seem to be on the cards in the near future.

The takeaway from all of this is that interest rates are unlikely to come down significantly any time soon. While November loan rates are high by the standards of the last decade, if we go back further, we find much higher rates: before about 2006, it was hard to find a loan with an interest rate below 20%--and average credit card rates have come down from 6% per month to 4% per month. The lower rates of the last 15 years have been large the product of the extremely low interest rates in the United States. This period looks to be over.