I started Dominicanomics as a way to provide solid background reporting on economic developments in the Dominican Republic for people outside the country. Over time, and as it has become imcreasingly popular with Dominicans as well, I have felt pressure to add more value and to be more thoughtful. I find it increasingly difficult to publish something interesting twice a week. And I see this problem with other newsletters I read regularly: it’s hard to be great on a schedule. So now, when I do publish, the pieces tend to be longer and more involved as well. And I enjoy writing this way as well. I hope you don’t mind the irregular schedule!

Over the last 10 years (2014-2024), the Doinican consumer price index has risen by 48%, averaging 4% per year (plus compounding). Pretty good. The consumer price index in the United States rose by 33%, or just under 3% per year. So what happened to the Dominican peso in that time, when tourism, remittances, and foreign investment were all rising strongly? It fell against the dollar by 37%! Why?

I don’t have the answer—or rather, I have too many answers. The one I think most needs exploring, though, is a possible lack of productivity growth.

The comparison of inflation differences with the exchange rate is a simple exercise. When economist analyze this issue, what they usually prefer to look at is not consumer prices, but rather production costs, specifically trying to calculate the cost of labor per unit of output. In a study from the early 1900s, what is now the U.S. Commerce Department sent a team to visit textile plants around the world. At that time, all of the textile industry machinery was made in a small area around Manchester, England, and it was exported around the world, often with Englishmen attached to run the new high-tech (for the time) factory. And yet, the English and American factories—where wages were highest--were able to outcompete factories in India, China, and elsewhere. Why?

What the American team discovered was that, in the U.S. and U.K., the factory gates would close promptly in the morning, and any worker not inside then would not be paid. Those inside would be assigned to monitor several machines. Elsewhere, workers (and others!) would wander in and out over the course of the day. And workers would have a single machines to tend. [1] Rarely are productivity differences so cut and dried, but they nevertheless exist.

I have recently been advocating for the Tax Department (DGII) to collect more tax revenue (but NOT for more taxes), and for more public investment spending. I am hopeful that this would provide a short-term boost to growth. In the longer term, though, what is needed is to raise productivity across the economy. How?

Let me start by, to paraphrase the film Casablanca, “rounding up the usual suspects”. Productivity growth in the Dominican Republic is hampered by four, widely-recognized, overarching problems:

The first problem is the education system. This is widely recognized, and why there has been a firm commitment (until now) to spend 4% of GDP on basic education. Unfortunately, the financial effort being made is not translating, for a variety of reasons (only some of which are easily fixable), into increased school achievement. And there is an especially important shortfall in technical education. Unfortunately, not much progress can be expected here, even in the medium term. A subject for another day.

The second problem is energy. A lot of progress has been made in supplying electricity in the past few years, but with losses so high that now deliberate blackouts are being implemented to reduce losses (and remember, meters stop turning when there’s no electricity. In the East, where power is supplied at a price to households of around RD$21 per kilowatt hour, outages are infrequent and usually quite short; in Santo Domingo, they are around RD$7 per kilowatt hour, but much less reliable. How much money is wasted on generator, batteries, and AC/DC inverters? And how much output/income is lost when there is just no power?

The third problem is transport infrastructure: Despite high taxes, high prices, and a ban on the import of old vehicles, there are probably too many cars, trucks, and buses (almost 2 million) on the road—and poor road maintenance is causing them to depreciate far too quickly. Outside of urban areas, greater road connectivity would also help. Progress is being made, but more is needed. And vast amounts of time and money are lost through endless traffic jams on the existing road network: public transport needs to be improved (and perhaps some traffic enforcement would help).

Finally, government regulation impedes productivity, especially in the financial sector. Anti money-laundering rules make it especially difficult to open a bank account (the World Bank’s famous “Doing Business” did not include this as an indicator, I presume because the Bank was contributing to the problem by pushing this). Moreover, taxation of non-cash financial transfers (0.15% of the amount transferred) keeps an important share of transactions in cash unnecessarily.

Work in these areas will take time to show results, but needs to be pursued urgently.

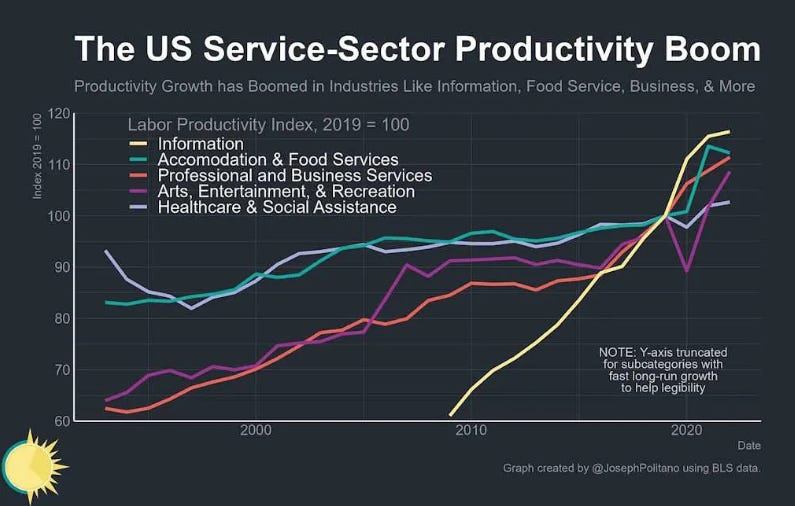

At the sectoral level, there are specific measures that can help improve productivity here or there. Data on productivity in the Dominican Republic is hard to come by, but this chart from the United States is instructive:

Even in service sectors, and with no major changes to the business environment, we can see significant productivity growth. Most notably, Accommodation and Food Services, which is so important in the Dominican Republic, saw labor productivity rise by about 25% over the past 30 years. This suggests that the same, or even more, is possible in the Dominican Republic.

This is where I should pull a rabbit out of a hat and announce the best way to improve productivity. If/when I come up with something, I will publish a “Part II” on productivity. I do believe that the long run of rapid growth driven by low-wage low-skill tourism and basic manufacturing is nearing its limits, and that a new strategy, one that reaponds to the four issues I note above, is urgently needed. In the meantime, is still useful to think about how that the inflation/exchange rate nexus responds to the problems of productivity.

[1] See Gregory Clark’s “Why Isn’t the Whole World Developed?” (Journal of Economic History, 1987) for further analysis of this episode.

Hi Wayne

while i can't argue with your points about taxation and productivity, i wanted to ask if there might also be some effect coming from the perceived instability of Haiti, not only from the outside (cruise, vacation destination and business investment-wise) but also domestically, as the population of the DR sees themselves forever joined in some way to Haiti's future and fate. As an observer from the U.S. I have heard zero news from the area since the last news frenzy of chaos and uncertainty. How could the DR govt improve its image in the world and at home? Is this even a thing?